Some time ago I reported on cement tiles in a brick villa from the 1930s and how a couple from Kamp-Lintfort on the Lower Rhine fell in love with a historic tile pattern. Now that I have more information, I would like to share it with you, dear readers.

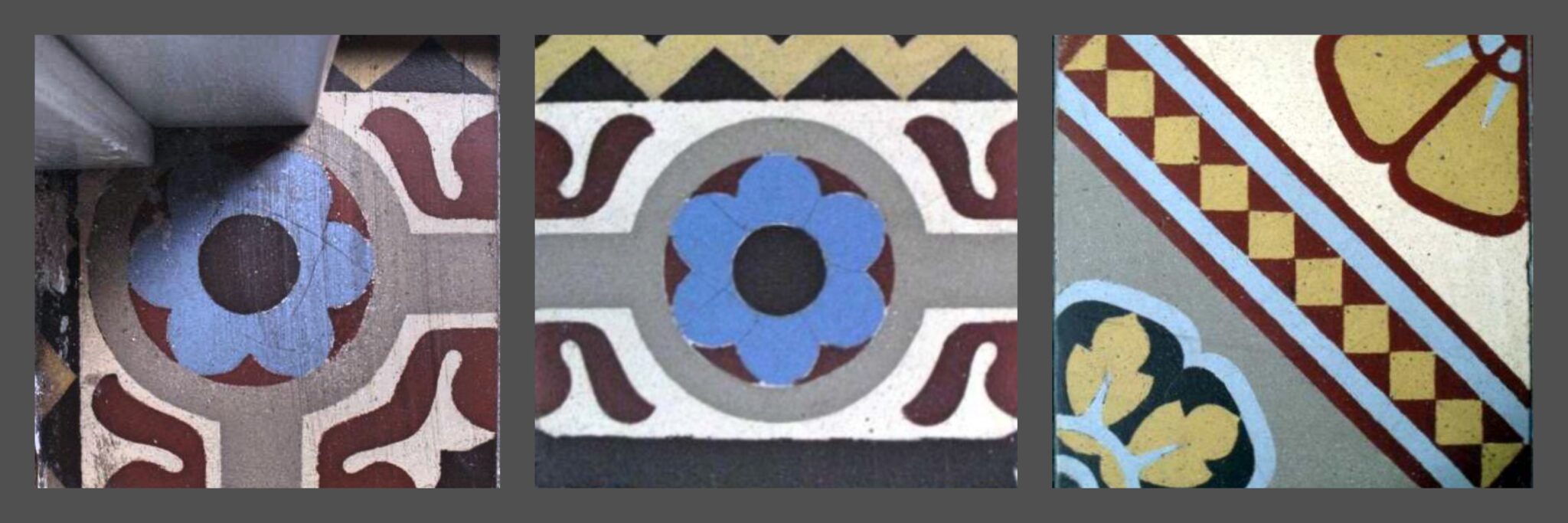

This picture inspired the couple when choosing.

This is the entrance to a historic house in Nettetal, also located on the Lower Rhine. A small area with historic tiles was still available and the owner decided to revive this pattern at MOSÁICO. Based on the original size of 14.2 cm x 14.2 cm, he opted for the dimensions of 15 cm x 15 cm. The pattern is numbered 252 at MOSÁICO, the border as number 484 and has the colors mahogany (M14), burgundy (M13), cream (M03), cinnamon (M35), mustard (M06), sky blue (M20) and light blue (M21). A monochrome mahogany border (M14) was chosen for this purpose.

Even this format, which is unusual for today's standards, indicates that the originals are stoneware plates. This type of floor covering was manufactured for around 70 years from the middle of the 19th century and was known in Germany primarily under the name “Mettlacher Platten”. The company Villeroy & Boch “invented” the process for producing patterned stoneware tiles in 1852 and founded its own factory in Mettlach in Saarland in 1869 only for the production of such floor tiles. There were other companies that manufactured such stoneware plates in England, France and Belgium.

Similar to the production of cement tiles Were the tiles madeby inserting a metal template with different sections into a frame. The individual compartments were filled with different coloured materials. Colored clay powder was used instead of liquid cement. Just as with cement tiles and in contrast to glazed ceramic tiles, the colored layer is a few millimeters thick and therefore the tile retains its color even under continuous tread load. There was also one masking template for each color, which covered all areas of different colors. Once the colors were filled in, the template was removed and the mold was filled with undyed clay. The slightly moist clay powder clumped together and could then be pressed together under great pressure. The resulting plates were then fired at around 1300° C for 190 hours, making them harder and more stable than granite. As a result of the firing, the pieces became a bit smaller, which is perhaps why the strange formats are created. There were also limits to the maximum size, as larger clay plates could easily warp or even crack during fire.

While Villeroy & Boch produced square plates with sides of 16.8 cm, the size of 14.2 cm is typical, among other things, of tiles from the Ransbacher Mosaik- und Plattenfabrik in Westerwald. I have now been able to confirm my assumption that the plates come from this manufacturer in Nettetal. During the renovation, the owner found a few individual panels that were used as filler under a window sill and thus escaped the rubble container during the modernization of the 1970s. They have the embossed company stamp on the back, an R surrounded by four stars. The presumed year of construction of the house, around 1895, falls during the first years of the company.

Die Ransbacher Mosaik- und Plattenfabrik was founded at the instigation of Luxembourger Paul Simons. Paul Simons had studied engineering in Paris and worked first at Villeroy & Boch in Mettlach, then he was the first director of the Boch Frères tile factory in Louvroil in northern France. In 1868 he founded his own tile factory in Le Cateau, also located in northern France on the border with Belgium. In addition to the clays mined locally, clays from the Westerwald were also imported from the outset. For this purpose, Simons had bought up land in Ransbach since 1876, on which sheds were built to dry various clays. In order to reduce costs, it was obvious to set up a tile factory in Westerwald as well. In 1881, the local newspaper read that a clay dealer had bought land on behalf of a French company to build a mosaic panel factory. In 1892, Paul Simons died suddenly at just 56 years of age; his shares were taken over by his widow Nelly Autier, his brother Félix and another Luxembourgish engineer, Gustav Nimax. The Ransbacher Mosaic and Panel Factory was finally built in 1893 opposite the railway station of the line opened in 1884 and initially employed around 200 workers, some of whom traveled from the surrounding area on workers' trains. The production of mosaic panels with inlaid patterns peaked in the years before the First World War. After that, in Art Deco and New Objectivity, simple geometric patterns and monochrome, as well as “flamed” (with streaks) and “porphyrized” (with speckles) tiles were preferred. Until the 1980s, the factory produced ceramic plates of various formats as well as utility ceramics.

At the turn of the 20th century, the patterns of the mosaic panel factory were based on the spirit of the time, historicism, which met the bourgeoisie's need for representation with a return to ancient and medieval models. But modern trends such as Art Nouveau were also implemented in tile patterns. The World Exhibitions, which took place in Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1867, 1878, 1889, 1900) and Chicago (1893), as well as national and international competitions, to which renowned artists submitted designs, also provided important impulses. Belgian designer Henry van de Velde has designed a 13-piece tile series for the Ransbacher factory.

Particularly magnificent tile patterns were often laid in the entrance area, where everyone could see it, including in the house in Nettetal.

This tile pattern is therefore not only suitable for the entrance, but it also makes a good impression as a stylish and fireproof “rug” for the fireplace in the living room. The warm colors reflect the warmth of the fire and at the same time harmonize with the plank floor of the living room, so that they have been inviting people to spend cozy evenings after work for over ten years now.